The lines of Iranians formed early every day. Often they came straight from the airport. They would line up outside the American consulate in the United Arab Emirates, hoping to make it under the cutoff. I was serving as the vice-consul in Dubai, just across the Persian Gulf from Iran, and it was my responsibility to manage the visa section. Most days I told Mahmud to stop the line at 200 applicants, but that day I had to make a prison visit, so I told him to make the cutoff 100. I knew how heartbreaking it was when he stopped the 201st person in line and said to come back another day. They lined up with such dreams of escaping in their head.

I didn’t yet know the details, but an American merchant marine had been arrested with narcotics and taken to the Al Awir detention facility. I was hoping to pay a first consular visit to him that afternoon. I knew from previous prisoners that in the UAE generally little food was provided. I didn’t want the possibility of this new prisoner dying of hunger in detention, so I decided to swing by the supermarket before calling on him.

It was 1986, and the Iran-Iraq war was at a bit of a stalemate. Both sides kept trying to surprise the other with new weapons — Saddam Hussein with chemical weapons; the Iranians with SCUD missiles. With the Iranian revolution in 1978, the hostage crisis in 1979 and the closure of the American embassy in Tehran, Iranians who wanted to travel to America had to find an embassy or consulate to pursue a visa.

My refusal rate was high, and while the United States was called “the Great Satan,” with Iranians chanting Magbar Amrikar! — “Death to America!” — during boisterous marches through Tehran, Mashhad, Bandar ‘Abbas and Shiraz, I learned that among Iranians waiting for an interview I was nicknamed shatan kucheq, “the little devil.” Since Americans couldn’t visit Iran, I felt reciprocity required that I turn away most Iranian applicants. The rare exceptions I made were generally older travelers who required a medical procedure available only in the U.S.

But with Iranian boys being forced to the war front in human-wave attacks, I did have qualms about refusing so many of them when they appeared at my visa window. Ayatollah Khomeini had broadened the definition of martyr to include anyone killed in the war, and I had learned that many boys — wearing red headbands with suras of the Quran on them — were forced to clear mines and assume other dangerous roles in the frontal assaults. I was conscious that by sending them back to Iran without an American visa, many were likely to die in the rush to overwhelm Iraqi forces.

Many of the boys were dressed as girls by their parents when they pleaded their cases to me. On the visa form, they often did not check either box for gender. Flying out of Iran as a girl was more likely to escape detection by the border guards, who were trained to stop most boys from leaving, although bribes were often paid to guards to look the other way or not to make a fuss. At the visa window, it wasn’t hard to see the boys’ masculinity peeking through the hijab. Many couldn’t hide well the fuzzy beginnings of a mustache, and it pained me to say no to them. Sometimes we would all laugh together as the boys tried to speak in a certain girlish falsetto to convince me of their femininity. Even their parents often smiled that they knew I knew that young Fatemeh was actually Shoja.

I was racing through the interviews that day, having granted only one visa to an elderly man from Isfahan who needed kidney surgery at the Mayo Clinic. I was getting near the end of the hundred applicants when Afsaneh, whose name means “fairy tale” or “legend,” approached the visa window with her parents. I knew right away that Afsaneh was a boy.

Afsaneh’s father pushed his bank documents and a copy of his house deed through the opening. The consulate translator said that Afsaneh, clad in a brown hijab with even her face shielded, had been accepted at an American college. The family presented the I-20 form required for a student to attend.

I asked Afsaneh what she wanted to study. Many students cited engineering or business, and I was used to refusing them. I had a special regard for those who wanted to study the liberal arts since I had double-majored in English and economics. Still, I very rarely gave any of them a visa since relations between Iran and the U.S. were at a nadir. When the translator told Afsaneh what I was asking, she paused and pulled the niqab away from her mouth.

Up to then, Afsaneh had spoken only in Farsi, so I was shocked when she recited Rumi’s poem “When I Die” in English. She mispronounced a few words — coffin as “co-fine” and lament as “lay-mint,” but I didn’t let that diminish my pleasure at hearing an applicant share the famous poem. Even some of the chatter in the waiting room died down as she recited the lines.

When I die

when my coffin

is being taken out

you must never think

I am missing this world

don’t shed any tears

don’t lament or

feel sorry . . .

it looks like the end

it seems like a sunset

but in reality it is a dawn

when the grave locks you up

that is when your soul is freed

have you ever seen

a seed fallen to earth

not rise with a new life . . .

when for the last time

you close your mouth

your words and soul

will belong to the world of

no place no time

To my staff, I used to say all the time, “You can tell when someone has done their homework.” And Afsaneh had done hers. I was impressed that here was someone who had intentionally prepared for the visa interview in such a powerful way. I don’t know that anyone was aware that I would appreciate such an act, but her recitation touched me deeply. I tried to imagine what she might look like without the hijab, dressed in a soldier’s uniform. I tried to understand how the voices of poets might be drowned out as waves of young Iranian boys pulsed forward into battle.

Rather than offering the customary answers of why a person wanted to go to America, here was a fresh reminder that if I refused the visa, this Afsaneh was destined for the killing fields, a poet forced into military service. I let her finish the poem, even though her mother encouraged her to stop when I closed my eyes to concentrate on the words.

The parents watched my face. I knew they were looking for a sign of how I might rule on the application. I didn’t say anything. I studied again Afsaneh’s application, and I asked the translator to tell me exactly what I was seeing on the father’s bank documents. I knew that many of these “official” papers could be bought on the black market, so I didn’t put much stock in their veracity. Afsaneh’s mother was crying and even her father seemed to wipe away a tear as the translator turned the pages of the bank records.

I left the visa window and went back to my office to think. Was it fair to make an exception for this “Afsaneh” who was actually a Houshang or an Ehsan or a Farhad? How could I justify letting this one Iranian through when I had stopped so many others?

Time was getting short, and I needed to buy food for the American prisoner and get to the jail. I returned to the visa window and huddled briefly with the translator. I told her to tell the family that I was issuing the visa, but that whenever Afsaneh returned to renew it, I expected her to share some of her writing with me. I could see the father grip his son’s shoulder through the hijab. In halting English, Afsaneh said, “Never I forget this day today.” I told her I wouldn’t either.

All these years later, an old man now, as my body weakens and I can sense my mortality approaching, I can close my eyes and hear again Rumi’s words in Afsaneh’s nervous recitation.

it looks like the end

it seems like a sunset

but in reality it is a dawn

when the grave locks you up

that is when your soul is freed

Recent Posts

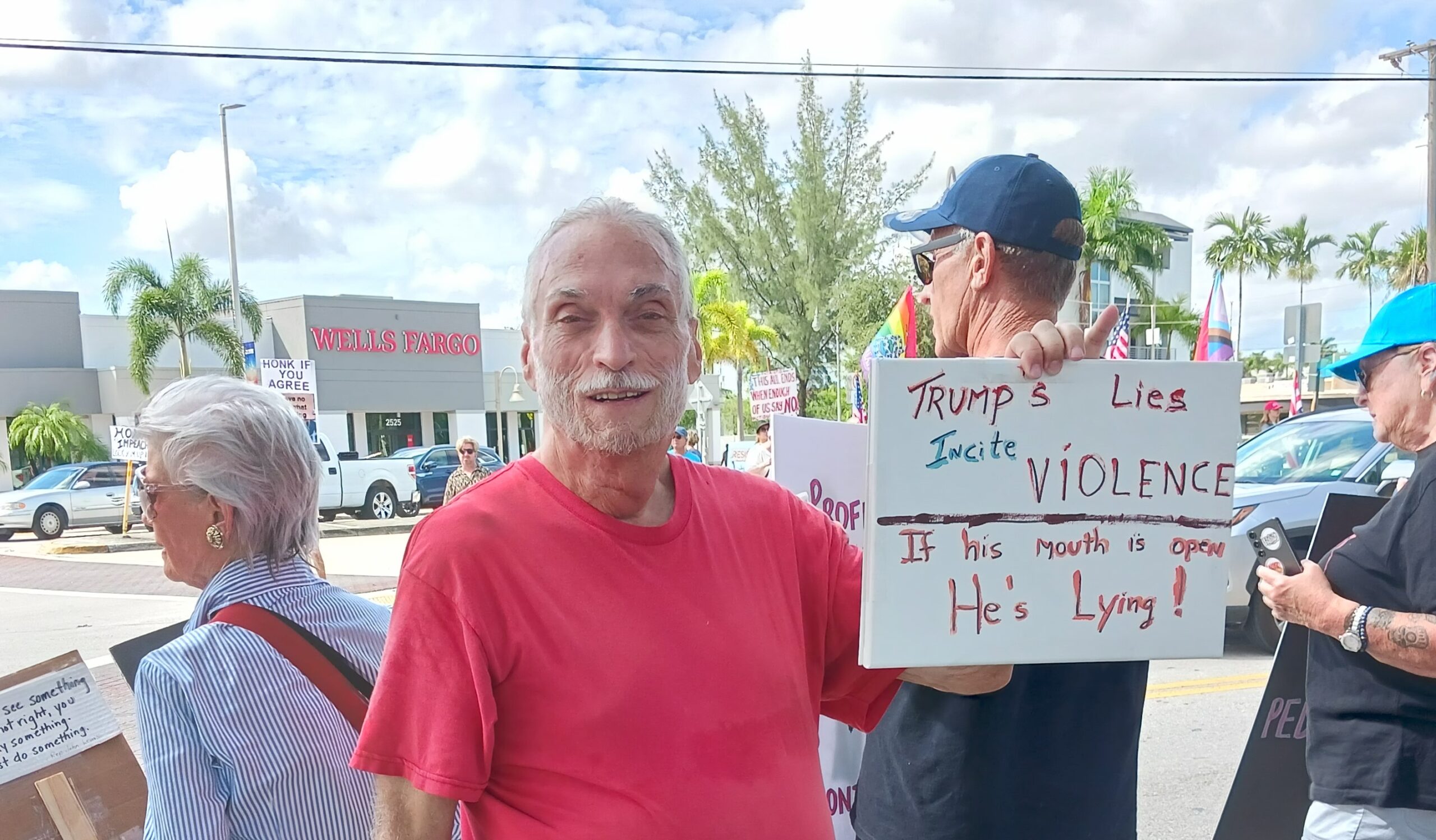

From Diplomat To Dissenter: Why I Protest Trump’s America

I love our country. I served as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Africa in the 1970s. I served as a Foreign Service Officer...

A Soul Set Free

The lines of Iranians formed early every day. Often they came straight from the airport. They would line up outside the American consulate...

A Cruel Season at the Bus Stop

The poem you’re about to read is not a quiet reflection—it’s a flare shot into the night. It emerges from a moment when...